This post is one of a continuing series to showcase some of the special objects we have as part of Holyhead Maritime Museum’s collection.

There are a number of memorial plaques on view at the museum. These were made of bronze and issued to the next of kin in remembrance of those lost during the Great War of 1914-1918. Each one is inscribed with the name of the person who died. Over one million were issued.

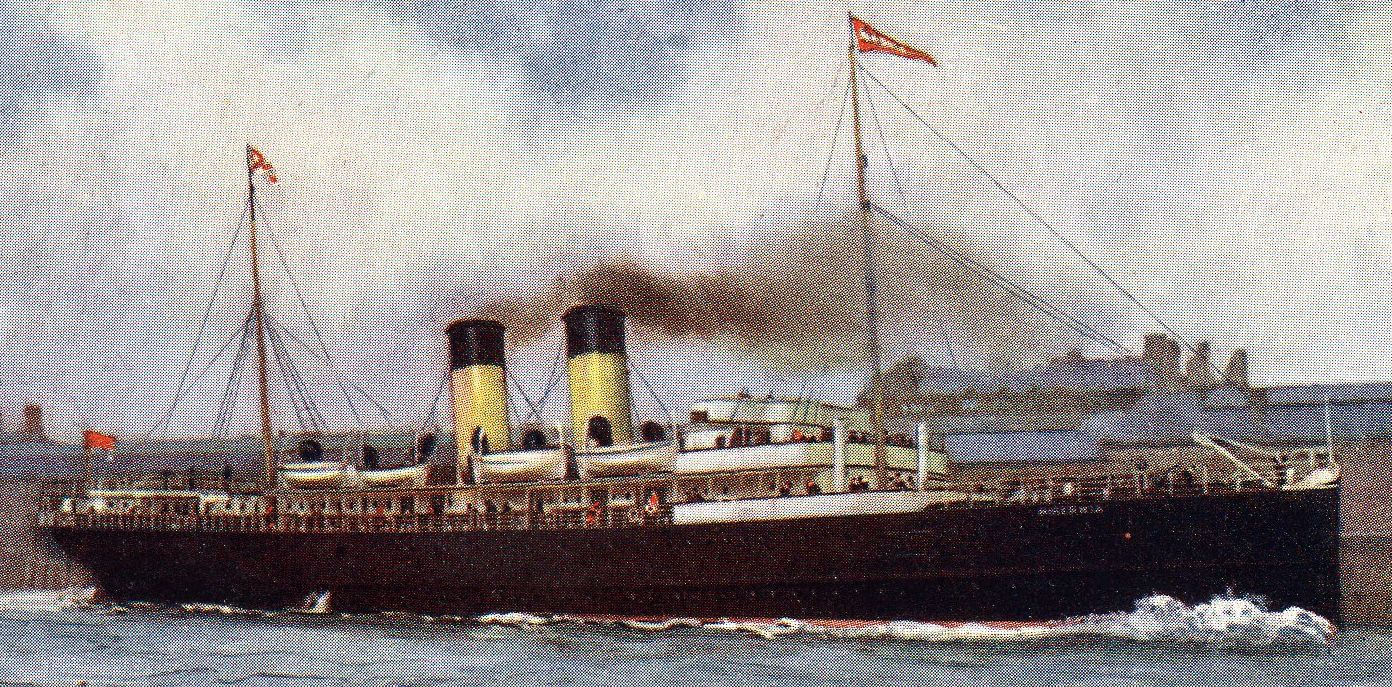

Only 600 were issued in memory of women who lost their lives due to the war. The plaque below is in the name of Stewardess Louisa Parry from Holyhead, who died in the torpedoing of RMS Leinster in October 1918. Whilst the ship was rapidly sinking she went to a lower deck to the aid of a woman and child but became trapped with them in their cabin as the waters rose.

The sinking of RMS Leinster resulted in the loss of over 650 lives including another Holyhead Stewardess, Hannah Owen. Both she and Louisa worked in hospitals before being employed by the City of Dublin Steam Packet Company. Hannah was 36, unmarried and had worked for the CoDSPCo for 12 years. She lived with her family at 2 Tower Gardens, Holyhead. Her Memorial Plaque was sold at auction in 2006.

Louisa, aged 22, was one of nine children, two of her sisters were also employed as Stewardesses, one of which was ill on that day and Louisa sailed in her place. The family lived at 5 Fairview, Holyhead. It is believed that Louisa was engaged and soon to marry an Army officer.

Hannah Owen and Louisa Parry

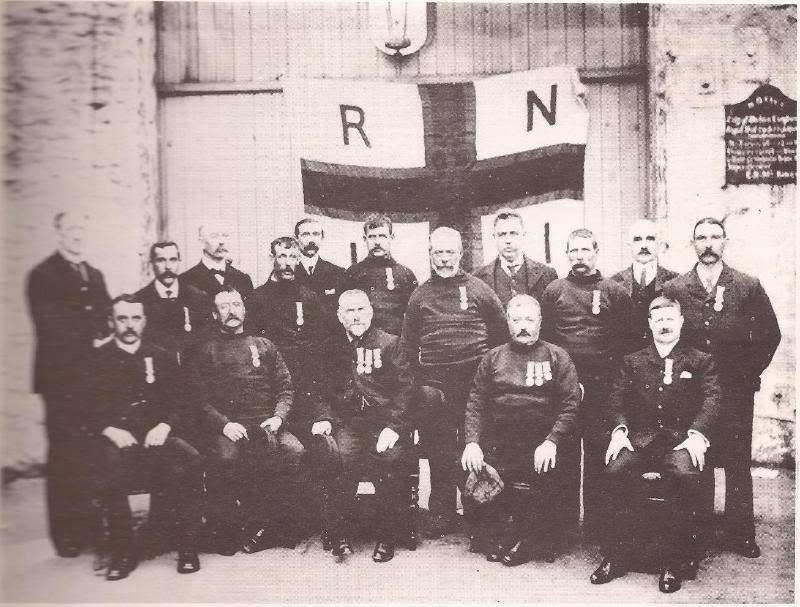

Hannah and Louisa were among a number of Holyhead women who worked as Stewardesses on the Irish Sea vessels operating out of the port. Each crossing had its dangers not only from the forces of nature but as the war progressed enemy submarines began to hunt and attack vessels of both the CoDSPCo and the LNWR. The official crew lists for 1915 include the names of 16 Stewardesses from Holyhead. Their duty, if the vessel was attacked, was to attend to the safety of women and children passengers, probably putting their own lives at risk.

The Great War also claimed the lives of two other Holyhead women. Margaret Williams was lost in the tragic sinking of the LNWR vessel, SS Connemara, at Carlingford Lough following a collision with SS Retriever. During a fierce storm and under restricted wartime lighting, this was one of the ship’s regular crossings from Greenore in Ireland to Holyhead. It is believed that this voyage was meant to be Margaret’s last before leaving to get married. She was then aged 32.

Annie Roberts from 6 Ponthwfa Terrace, Holyhead joined the WRAF in May 1918 and was based at Hooton Hall, Cheshire. Aged only 20, she was one of many who sadly succumbed to the influenza epidemic.

The 1920 book ‘Holyhead and the Great War’ by R E Roberts records that 62 women from the town served in uniform – WRNS (4), WAAC (12), National Army Catering Board (8), Land Army (12) and Munitions (26). In addition, close to 40 women served as part of the Red Cross effort in the many hospitals and convalescence homes of the area.

Not all Holyhead’s losses are recorded on the town War Memorial (The Cenotaph). Catherine (Katie) Evans, from Bryniau Llygaid Farm, Holyhead, was a volunteer nurse for the Red Cross Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) based at Holyhead during WW1. Katie served with the No. 8 Anglesey Detachment but sadly died on 16 October 1914. Although not commemorated on the Holyhead Cenotaph, she is listed on one of the panels in York Minster commemorating members of the nursing services. Katie was unmarried and only 34 years old when she died following an operation for a perforated ulcer. On the day after her funeral, her sister Pollie Evans volunteered for the VAD.

Contributed by the Editor.

With special thanks to Simon and Jon McClean who donated the memorial plaque of their great-aunt, Louisa Parry, to the museum and also allowed her photograph to be published.

Note: When the memorial plaques were first designed it was not envisaged that they would be needed in memory of women and modifications were necessary to change the ‘HE’ into ‘SHE’. To enable the ‘S’ to be added a much narrower ‘H’ was inserted to make space for it.

© Holyhead Maritime Museum

This series of posts is to showcase items from the museum’s collection and to support the ‘Ports, Past and Present’ project that features and promotes five ports of the Irish Sea connecting Wales with Ireland – Rosslare, Dublin Port, Holyhead, Fishguard and Pembroke. More information here – https://portspastpresent.eu/